By Michelle Boutell

The USAID-funded John Ogonowski and Doug Bereuter Farmer-to-Farmer (F2F) Program provides technical assistance from U.S. volunteers to farmers and agricultural groups in foreign countries to promote sustainable improvements in food security and agricultural production, processing, and marketing. The Cambodian Farmer-to-Farmer project is administered by the Smith Center for International Sustainable Agriculture in partnership with the Center of Excellence on Sustainable Agricultural Intensification and Nutrition (CE SAIN). This project promotes the integration and productivity of vegetables, fruit, and livestock in food systems in Cambodia through short-term exchanges between skilled American volunteers and farmers, farm groups, agribusinesses, NGOs, and universities. These exchanges place American volunteers with Cambodian host-organizations for two-week assignments to respond to local requests for technical assistance.

Carl Bannon is an extension expert with over 20 years of experience in both the private and public sectors. He’s volunteered on nine different Farmer-to-Farmer assignments in countries including Nepal, Tanzania and the Republic of Georgia, in addition to remote assignments with partners in Ecuador, Honduras, Nigeria and Cambodia.

Q: What motivated you to use your skills in this kind of volunteer work?

I’ve always wanted to work in countries where they could really use the information to improve their quality of life. I knew there was a huge need for better management of crops in general, not just pest management, but nutrient management, water management. I was always interested in helping others that didn’t have the privilege I had.

Working to help foreign countries improve their agricultural systems is a family tradition for Carl; his grandfather, David M. Thorpe, led some of UTIA’s earliest international work.

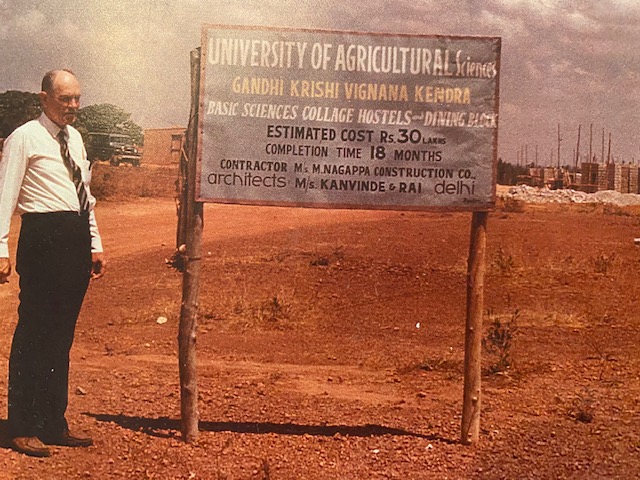

My grandfather led a team of agricultural scientists in the late 60’s in India. He was also a professor of ag economics at UT. We had a family farm in Western Tennessee, but he was an extension professor of ag economics in Knoxville for 33 years. Prior to that, he was an extension agent and was assistant director of the Tennessee extension service. In 1967, he went to India as Chief of Party of a USAID-funded project and led a team of university extension specialists. He lived there for four years, until 1971. They were introducing new higher yielding varieties and all the management required to take advantage of those varieties. So I was always interested in and inspired by what he was doing.

This was right around the time of the Green Revolution– a period of time that saw greatly increased crop yields as a result of technology transfer initiatives, contributing to widespread reductions in poverty, reduced hunger for millions and declines in infant mortality around the world. During this time, Bannon’s grandfather and his team were in Bangalore, India. They worked out of an experiment facility they’d established in Mysore. Bannon explained more about what that research looked like for his grandfather and his team:

This facility was similar to CESAIN in Cambodia– they had research and extension facilities to introduce new technologies. In their case it was new corn, but they did a lot of millet and I think they did rice. This was during the time that American agronomist Norman Borlaug was introducing new wheat varieties adapted to tropical environments.

These new crop varieties alongside improved management practices transformed agricultural production in Latin America and Asia, sparking what has become known as the “Green Revolution.” The Farmer-to-Farmer program facilitates the kind of agricultural information sharing that continues to help farmers around the world improve their production systems.

Q: Tell us more about what you were working on in Cambodia.

Most of the training was at the CESAIN facilities in Siem Reap, in Northwestern Cambodia. The volunteers each had a day to present on an assigned training topic, so there was a day on soil management, a day on IPM and a day on irrigation management. We had time in the field as well as time in the classroom to instruct participants. So we had a lot of different people there, mostly extension-type workers from NGOs, seed companies, universities, and the Ministry of Agriculture (MAFF). A lot from the Royal University of Agriculture.

Q: How can agricultural experts in the private sector contribute to the Farmer-to-Farmer volunteer mission?

Often the private sector is the one introducing the new technologies. In the past twenty, maybe thirty years, I think a lot of the newer technologies have been coming from the private sector. They have internal extension agents in their companies, and that’s a lot of what I was doing, training farmers to use new products and practices. A lot of companies moved to having an internal extension educator, where they’d be training their own sales teams and agronomists as well as growers and partnering with public extension staff. I found that a lot of times in these F2F projects that they want to partner with the private sector because those are the people that are on the farms all the time, more so than a lot of the extension agents. Few countries’ public extension system have the agency to reach farmers that we have in the U.S.

Q: In what ways do you think that professionals can benefit from volunteering in these kinds of programs?

I think it benefits any individual to go to another country and see the conditions that growers there are working in. It’s humbling for people from the United States that live a relatively privileged life to go and see how the rest of the world is currently growing their food, and work with them where they’re at; and at the same time, learn from them how to do more with less.